The following guidelines should be taken into consideration when preparing to do an examination and condition report: Safe handling practices during condition reporting are critical to the preservation of the work of art. CCI Note 10/13 Basic Handling of Paintings describes the safe handling of paintings, both framed and unframed. It also gives. MAIN REPORT FOR LOAN. ARTWORK Artist Title. Loan ref: LENDER & EXHIBITION DETAILS Name Exhibition Title. Open Date Close Date DESCRIPTION. Describe the work and list the elements/components. MEDIA ELEMENT. Describe the number/format and status of the media elements and fill in additional template and attach. The process diagram and documents for loans are guidelines and templates for owners to follow when borrowing and lending media art. The documents include sample templates for exhibition budgets, condition reports, facilities reports, installation documents and loan agreements. They seek to update existing practice for more traditional art.

- Art Condition Report Template Guggenheim Pdf

- Art Condition Report Template Guggenheim 2017

- Art Condition Report Template Guggenheim Report

When he got to Bilbao a month before it opened, says Frank Gehry, “I went over the hill and saw it shining there. I thought: ‘What the fuck have I done to these people?’” The “it” is the Bilbao Guggenheim museum, which made both its architect Gehry and the Basque city world-famous. Its achievement, measured in much-repeated metrics of visitor numbers and economic uplift, in global recognition and media coverage, in being, in effect, an Instagram sensation long before anyone knew what that might be, is prodigious. It revived belief that architecture could be ambitious, beautiful and popular all at once, yet Gehry has always said that its success took him by surprise.

Supersonic. The museum was opened 20 years ago this month, by the king and queen of Spain, since when it has become the most influential building of modern times. It has given its name to the “Bilbao effect” – a phenomenon whereby cultural investment plus showy architecture is supposed to equal economic uplift for cities down on their luck. It is the father of “iconic” architecture, the prolific progenitor of countless odd-shaped buildings the world over. Yet rarely, if ever, have the myriad wannabe Bilbaos matched the original. This is probably because it came about through a coincidence of conditions that is unlikely to happen again.

Despite Gehry’s protestations of surprise, it is a project that has fulfilled its original intentions with precision. Juan Ignacio Vidarte, the museum’s director, whose involvement dates back to the time of its inception in the early 90s, says that it was meant to be “a transformational project”, a catalyst for a wider plan to turn around an industrial city in decline and afflicted by Basque separatist terrorism. It was to be “a driver of economic renewal”, an “agent of economic development” that would appeal to a “universal audience”, create a “positive image” and “reinforce self-esteem”. All of which it pretty much did. It has been rewarded with a steady million visitors a year, the 20 millionth having arrived shortly before the 20th birthday.

Gehry, who beat two other architects in the competition to design the building, recalls that he was asked to design what was then not called an icon. He was nervous. “They said: ‘Mr Gehry, we need the Sydney Opera House. Our town is dying.’ I looked at them and said: ‘Where’s the nearest exit? I’ll do my best but I can’t guarantee anything.’” So he came up with the convulsive, majestic, climactic assembly of titanium and stone, of heft and shimmer, a cross-breed of palazzo and ship that also flips its tail like a jumping fish, that now stands on the bank of the river Nervión.

It was not a wholly new set of ideas – Sydney, indeed, had demonstrated the value of the transformative landmark, as had Paris with the Pompidou Centre. Frankfurt, Glasgow and Pittsburgh had striven to raise themselves with culture and/or museum-building. What set Bilbao apart was the degree of contrast between the city’s lowly status and the artistic and architectural ambition of its proposed flagship.

They found an ally in the Solomon R Guggenheim Foundation of New York, which had previous in commissioning icons from architects named Frank, in the form of Frank Lloyd Wright’s white spiralling museum on Fifth Avenue. It was then run by Thomas Krens, the holder of an MBA from Yale and a man formed by the risk-taking, deal-making culture of the 1980s. The Bilbao people had heard that the Guggenheim wanted to expand its European presence, and plans to do this by adding to the Peggy Guggenheim collection in Venice weren’t “going forward sweetly”, as Vidarte puts it, so they offered their battered city in place of La Serenissima. The Guggenheim, he says, liked their ideas and their seriousness.

An agreement was worked out, an early instance of the international trading of museum brands that also engenders, for example, the forthcoming Louvre Abu Dhabi, whereby the governments of the city, and of the province and region in which Bilbao stands, would pay for construction, and contribute to acquisitions and running costs. The Guggenheim Foundation would lend its name, works from its permanent collections and its management and curatorship. The arrangement wasn’t universally popular – it was called “McGuggenheim”, an act of cultural imperialism paid for by the people it subjected – but it gave Bilbao access to the high-quality art without which a museum would be pointless.

The Canadian-born Gehry, now aged 88, was then in his 60s, and he had a high reputation in the architectural world for his imaginative reinterpretations of the everyday structures of his adopted home of Los Angeles. He didn’t have the celebrity he gained later (an appearance on The Simpsons, for example), and although he was known for the freedom of his forms, the public hadn’t yet seen much of the complex, multiply curving shapes which, since Bilbao, are assumed to be his trademark.

They were, however, brewing in some of his projects, especially an $82m house for the Ohio insurance magnate Peter Lewis – a trustee of the Guggenheim foundation from 1993 to 2005, its biggest donor, and the man who introduced Gehry to Krens — that was designed and redesigned but never built. Gehry and his office pioneered the use of CATIA, software originally developed for designing aircraft, which allowed elaborate shapes to be made without prohibitive cost. It enabled him to realise the Bilbao Guggenheim, as he is keen to point out, within its $100m budget. “I could have straightened everything out,” he says, but “it wouldn’t have cost less.”

The ability of computers to design unfeasibly elaborate buildings has since multiplied. It is a ubiquitous and defining feature of contemporary architecture. It has been an effective accomplice of post-Bilbao “iconic” architecture which, although sensible architects have been pointing out its weaknesses for almost as long as it has existed, and although it suffers from an obvious hyperinflation of shape – if everything looks abnormal it becomes normal – shows no sign of going away.

This long-running craze would have happened in any case, but the Guggenheim gave it fuel. Its influence takes two main types. In one, public authorities – in West Bromwich, in Denver, in Metz – seek to use some version of the “Bilbao effect” to “kickstart” (as it is often horribly put) regeneration. In Spain, in the bubble years, cities became particularly fond of monuments whose appearance outran their content, architectural dumb blondes by Santiago Calatrava or Oscar Niemeyer or Peter Eisenman that looked especially redundant when the crash came. In the other type, private developers use funny shapes as marketing tools for their towers – see the skylines of Dubai or many Chinese cities, or London’s car boot sale of domestic gadgets.

What both approaches, public and private, have in common is the use of spectacle to distract attention. Public authorities might not want you to notice that their regeneration plans are flimsy. Developers typically use eye-catching design to justify their stretching of planning restrictions, or to obscure the fundamental sameness and ordinariness of their products, or to sell buildings before they are realised – in some cases too to deodorise the dirty money that pays for the projects.

The use of spectacle was also the basis of the most sustained critique of the generally lauded Guggenheim, that its powerful look makes it a poor setting for art. For the critic Hal Foster, speaking in Sydney Pollack’s film Sketches of Frank Gehry, the building trumps the art it is supposed to serve: “he’s given his clients too much of what they want, a sublime space that overwhelms the viewer, a spectacular image that can circulate through the media and around the world as brand”.

Gehry is familiar with the criticism and pushes back. All his professional life he has known and worked with artists. “In the beginning,” he says, “I thought architects should make neutral spaces for art. But my artists were saying: ‘Fuck off, we want to be in an important building. I want to go home and tell my mother I’m in the Louvre.’” He reels off the artists who he says liked the Guggenheim – Anselm Kiefer, Sol LeWitt, “even” Robert Rauschenberg. He says that a clique of museum directors, meeting in London, “passed a resolution that they should never build a building like Frank Gehry’s… they pretty much kept to it.” He claims that the same directors – “you know who they are” – told Cy Twombly never to show in Bilbao. He did, eventually, two years or so before his death. “Cy called me and said it was the best show in his whole life.”

Gehry is also keen to distance himself from the dumber aspects of the building’s architectural legacy. “I apologise for having anything to do with it,” he says. “Maybe I should be hung by the yardarm. My intention was not that it should happen.” Talk of the “Bilbao effect” makes him cringe – “it’s bullshit.. I blame your journalist brethren for that.” He wants to stress an aspect of the design often overlooked by imitators, which is that it works hard to connect to its surroundings: “I spent a lot of time making the building relate to the 19th century street module and then it was on the river, with the history of the river, the sea, the boats coming up the channel. It was a boat.”

Vidarte, too, is uneasy about its influence. He’s “flattered”, but at the same time “concerned and nervous… many people are just trying to replicate its most superficial aspects.” The project was not about the building, he says, but also a “sustainable” plan for its management and content, and the regeneration of Bilbao was not just about the Guggenheim but also about investment in infrastructure and other urban essentials.

Alongside Gehry’s building stands a giant puppy, covered in living flowers. It was created by Jeff Koons and “underwritten” by Hugo Boss. Shortly before the opening three Basque separatist terrorists tried to disguise themselves as gardeners so as to plant explosives in it. They were foiled, but a policeman died in the ensuing shoot-out.

The incident was emblematic. It was evidence of the troubles that Bilbao was trying to escape and which have indeed diminished. The Koons-Boss pooch, charming and calculating at once, was an early manifestation of the sort of global, big-money, market-led, spectacular art culture that has now become familiar, for which the Bilbao Guggenheim was certainly a Trojan horse. Krens himself went on to be a controversial and ambitious protagonist of this culture, if not an entirely successful one – his Guggenheims planned for Rio de Janeiro, Las Vegas, Guadalajara, Taichung, lower Manhattan and Abu Dhabi have mostly failed to materialise, or stuttered if they did.

But to lay on the Bilbao Guggenheim the effects of its legacy is an injustice to what it was and is. From the political, cultural and commercial currents of its time, not all of them noble or elevated, it drew the energy to make a phenomenon that few people would wish away, least of all Bilbao itself. Its true lesson is that it can’t be copied, because it came from circumstances that were unique.

Five would-be icons

Centre Pompidou-Metz, France, designed by Shigeru Ban, 2010

As in Bilbao, a famous art institution created an architecturally conspicuous outpost in an unglamorous city.

The Public, West Bromwich, designed by Will Alsop, 2008

An attempt to revive the West Midlands with a “box of delights”, where people could both experience and make art. It is now a sixth-form college.

Centre Niemeyer, Avilés, Spain, designed by Oscar Niemeyer, 2011

A cultural centre designed by the celebrated Brazilian architect in his 90s, it closed for financial reasons soon after its completion, but later reopened.

Ordos museum, China, by MAD Architects, 2011

A museum and landmark for a city in the Gobi desert, whose redevelopment is famously underinhabited.

Louvre Abu Dhabi, designed by Jean Nouvel, 2017

Due to open in November, the latest marriage of a museum brand with an aspiring city, celebrated with dazzling architecture.

- This article was amended on 4 October 2017. It had originally stated that the giant puppy outside the Guggenheim had been there only temporarily

The conservation and restoration of time-based media art is the study and practice of conserving time-based media and its components. The conservation and restoration of time-based media art is a complex undertaking within the field of conservation that includes understanding both physical and digital conservation methods; there are many facets of time-based media conservation. Its major aim is to detect and monitor short and long-term changes that an artwork may undergo in response to its environment, technological developments, exhibition-design, or technicians' preferences.[1]

- 2Preservation and conservation strategies

- 2.1Preventative measures

- 2.2Examination and documentation

- 2.3Research

- 2.3.1Research projects

- 2.4Treatment

- 2.5Education and outreach

- 3Education and training

Time-based media art[edit]

Time-based media is any media that takes time to view, in other words it has a dimension of duration (e.g. five minutes and 10 seconds). Time based-media also contains a technology component, as hardware will be required to view the work.[2] Time-based media art may be made on a physical media, such as film stock, by a digital means, or a combination of the two. Examples of time-based media include artworks and installations composed of video, audio, film, slides, software-based art or other forms of technology-based artworks.[2] A time-based media artwork will consist of the medium- for example a video tape or DVD, the equipment it is played on, and any additional installation components.[3]

Works containing video and/or audio may at times be referred to as '4D' (four-dimensional), referencing time as the fourth dimension, in addition to the other three dimensions in artwork: length, width, and height. Some time-based media works may overlap, in some respects, with New Media Art. Other terms that may also refer to time-based media art include 'variable media art', 'electronic art', 'moving-image art', 'technology-based art' and 'time-based media'. Time-based media collections may be housed in libraries and archives, but time-based media art collections are typically housed in museums, where film and video are collected as fine art and where the collection is typically smaller than in a library or archive.[3] Museums are more likely to collect video and installation-specific equipment as well.[3] The majority of time-based media art is completed on noncommercial films stocks, such as 8mm or 16mm, on videotape, or via a digital means. Time-based media art is differentiated from professional or commercial film-making.

Preservation and conservation strategies[edit]

Guidelines for collecting and preserving time-based media art are still evolving, and standards have not yet been reached.[3] Generally though, video and film must be looked at differently because of the difference between the two mediums, despite having the similarity of being recorded in time. Thus procedures for preservation and conservation will vary between the mediums. Video is a coded system, the information stored on the magnetic or digital tape can be retrieved only with a specific electronic playback device; the images on the film strip, however, are legible on their own, though the projector provides the only means by which they can be viewed.[3] When collecting film and video art, a master and at least one sub-master should be obtained. In some cases, and exhibition copy will be obtained as well, in other cases it will be copied by the museum. The Guggenheim Museum provides preservation models for Analog Standard Definition Video, Digital Standard Definition Video, and High Definition Video. Some conservators recommend that sub-masters be in digital format, as analog tape suffers from generation loss, each time it is duplicated.[3] Digital formats can suffer from generation loss as well, but it can be avoided through good practice. The sub-master will be used to make new copies of the work and the format of the sub-master needs to be updated when it nears obsolescence. Obsolescence is of particular concern to time-based media art conservationists as many artworks are tied to hardware which is no longer manufactured or supported. File formats reaching obsolescence are another concern, as operating systems change and old formats are replaced by newer ones. Fortunately there are some methods in place to help prevent the total loss of time-based media artworks.

Preventative measures[edit]

The protection against physical loss, technological obsolescence, and digital loss of the file are important aspects of a holistic approach to preservation strategies. Measures must also be taken against environmental factors, such as humidity and pests to ensure the long-term preservation of any physical media. Integrated Pest Management is an important part of any museum preventative conservation plan. It is important to note that preventative measures do not stop deterioration fully, they merely prolong the time it takes for the media to deteriorate. Some media, like certain film stocks, are more stable than others, and some media, such as magnetic videotape are potentially unstable, so again different approaches will be necessary.

Storage and maintenance of physical objects[edit]

Good storage practices help ensure the long-life of an artwork and should be incorporated into a museum's conservation strategy. Storage practices vary by media, so a museum will need to employ a range of storage options to best care for their time-based media art collections. A variety of physical media, such as film, tape, and disks must be stored properly to prevent physical loss. Prevention is the best measure of protection against loss. How media is stored will be dependent on the type of media it is, film has different considerations than disks or videotape. Generally, time-based media storage will require cool temperatures and low humidity.[4]

Film - film reels are typically stored in their metal or plastic canisters, laid flat, and stacked on top of each other. Film must be stored in a climate-controlled room due to its susceptibility to heat and humidity. Film may also have additional special storage considerations, which may involve low temperature freezes to retard further damage.[5] How stable the film is depends largely on the type of stock, but film, if well taken care of, is generally able to last for long periods of time. Film has been made on a variety of materials, including nitrate-based stock (see: Nitrocellulose) and acetate-based stocks, and polyester-backed film, each have their own considerations. Nitrate film must be handled carefully, as it is highly flammable; cellulose acetate film stocks are at risk of vinegar syndrome, whereas polyester-backed films are not.[4] Film is stored in a colder environment than other time-based media, and different types of film have different optimum storage temperatures. 'Color film should be stored at the coldest possible temperature to reduce fading,' 0-30 degrees Fahrenheit, while black and white film can be stored at a temperature of 25-50 degrees Fahrenheit.[4]

Magnetic Videotape- Magnetic videotape was never meant to last, and often has a short life (often only a few decades) especially if exposed to warm or humid conditions.[3] Videotapes, should be stored in upright, under cool, dry, dust-free conditions.[3] Videotapes may be stored in polypropylene cases, but without paper inside the cases and 'magnetic media should never be stored at temperatures below 46 degrees Fahrenheit'.[4] Magnetic media should also be kept away from magnetic sources, which could demagnetize them.[4]

Optical Digital Media - DVDs and CDs are another media that will need storage space. Optical media should be stored in hard plastic jewel cases or other inert plastic containers; avoid storage in plastic sleeves. DVDs and CDs can be stored at temperatures ranging from 62-68 degrees Fahrenheit, with 33-45% relative humidity, but cooler temperatures are recommended to ensure a longer life.[4]

Playback Devices - Because time-based media is dependent on technology to view it, playback devices must also be stored. There are some devices that will apply to many works in a time-based media art collection, but specific types of technological devices may be required for the art or preferred by the artist. Maintaining the technology that the time-based media art is played on is one conservation strategy, and what is stored depends on the device. Consumer products, for example, are not meant for repeated viewing on such a large scale and are usually not expected to have a long enough life to maintain the device well into the future. Due to rapid changes in video technology and the high cost of maintaining and storing equipment, storage and maintenance of some playback devices may not practical for a museum as a primary strategy.[3] Museums do at times need to store obsolete technology though, such as VCRs, old computers, video game systems, etc., particularly if they have been customized for the artwork by the artist. In these cases, conservation strategies could included acquiring spare parts (early on in the acquisition process, before the technology goes out of manufacture), making new components if necessary, and/or 'recreating significant features by inexact substitution' (in order words, using the 'best match').[6] Until better solutions are found, keeping and maintaining old technology will remain a necessity. Unlike video equipment, film equipment is far more stable and museums may be more likely to conserve the equipment along with the media because there is less upkeep and film equipment does not need constant replacement due to obsolescence.[3] A working projector will always run film. Technological devices should be stored in a clean, climate controlled environment, as humidity can be damaging to electronic components.

Digital preservation[edit]

Digital files must be preserved and stored as well, otherwise they also risk degradation. Due to the large amounts of storage space that may be needed, museums may want to employ the use of a digital repository that offers digital preservation as a service. Repositories will keep the digital file stored, perform migration (moving the old format to a new, usable format), and typically offer some guarantee of preservation for a specified period of time. Artists may also wish to seek out a repository for storage of their digital artwork. Rhizome's Artbase is an online archive that seeks to preserve contemporary digital art. Part of digital media storage is to ensure continuity of the digital file through format changes, thus migration becomes a likely strategy. Some conservators recommend that medium upgrades take place at least every five years, making duplication a main strategy of digital conservation.[3]

Time-based media art that either has an inherent digital component (i.e. a born-digital work) or has been digitized will have the need to be preserved digitally. While this work may not entirely be completed by the conservator, conservators will be aware of the methods used to preserve digital media. The Variable Media Approach, a strategy that comes from the Guggenheim Museum's Variable Media Initiative research, offers a way in which to define the artwork 'independently from medium so that the work can be translated once its current medium is obsolete.' [7] It is a methodology that approaches a work as independent from its media, so that is may be thought of as a behavior and not something tied to its hardware.[8] This process looks to preserve works despite the uncertainty of technological developments of the future. By making a work independent from its medium, the Variable Media Approach hopes to ensure the life of the artwork well into the future, beyond the obsolescence of all current technology. The approach encompasses four aspects: Storage, Migration, Emulation, and Reinterpretation.[9] Storage is the most basic strategy. Migration simply means to copy the files to new storage media. With migration, conservators preserve the original aspects of the work. Emulation is not as straight forward, it involves some amount of interpretation and is more an imitation of the original work. In the context of digital media, 'emulation offers a powerful technique for running an out-of-date computer on a contemporary one'.[9] Reinterpretation is the most radical strategy, as it involves recreation of the work.[9]

When formats or storage media become obsolete, 'time-based art is typically migrated to newer, accessible platforms'.[10] This will mean updating the file format so that it is playable on newer technology. In some cases, this may not be in keeping with the artist's wishes, as he or she may wish to continue viewings of their work in a specific format. If the format is integral to the work, then upkeep becomes more involved and maintaining the usability of the artwork against the odds of obsolescence in both media and technology becomes a major preservation challenge.[10] For this reason, it is encouraged that artists allow for some flexibility in future iterations of the artwork.

Examination and documentation[edit]

Examining and documenting the physical state of an object is an important part of understanding its overall condition. The process of examination and documentation will alert conservators to any problems that need immediate or future attention.

Physical examination[edit]

The physical components of time-based media art must be examined in order to understand their physical condition. With film, physical examination will identify a variety of deterioration processes, such as vinegar syndrome in safety films or color dye fading in color film stock. It is important to identify these early, not only to try to prevent further deterioration, but to intervene with treatment or to make a duplicate copy. Without the examination process, time-based media may degrade beyond repair and possibly be lost entirely.

Condition assessments[edit]

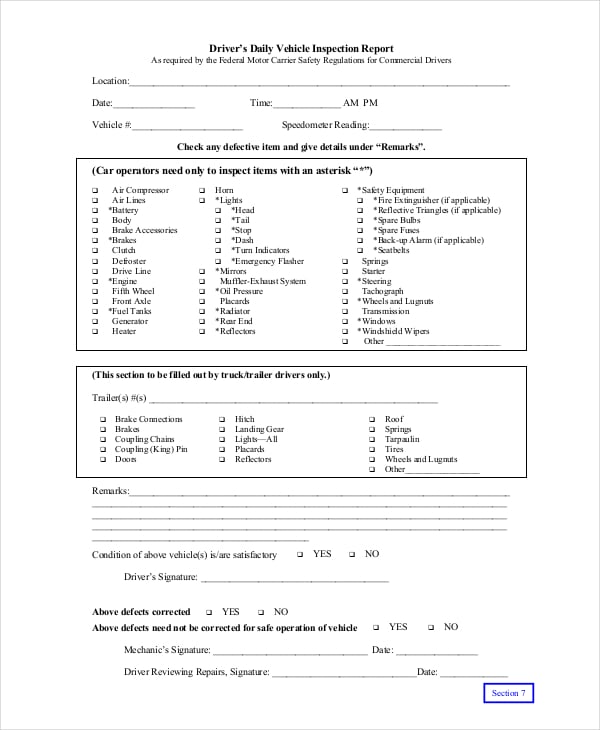

Condition assessments are procedures that are carried out by conservators or other collections care professionals to document the overall condition of an object. These assessments are necessary for all the types of media and technology associated with time-based media art. The assessments stay in the object's file and give future conservators insight into the object's life history. They are performed upon intake of an object into a collection, before and after the object goes on loan, and as necessary. They make note of any physical issues that may be present, such as tears, stains, scratches, or other damage. Film is especially vulnerable to tears and warping, while DVDs and CDs scratch easily. Other issues cannot be seen, such as demagnetization of tape, and require other methods of examination. After the condition of a physical object is assessed, the examiner may recommend treatment if necessary.

Independent Media Arts Preservation (IMAP) recommends taking certain steps to assessing the condition of time-based media: 1) Examine the container - damage on the outside of a container could mean damaged media inside the container. Cases should be examined for dents, stains, and molds or fungus. 2) Check for odor - it may be an indication that the media has deteriorated. Vinegar syndrome emits a vinegar-like odor when present. If media smells musty it could indicate magnetic decay. 3) Examine the surface and the edges - look for powder, dust, dirt and residue, they may indicate deterioration or surface contamination. 4) Identify the format - Knowing the media format is important to proper handling. 5) Play the tape - In some cases it may be necessary to play the tape, a process that if not handled carefully could damage the media. Playback can detect 'noise, color shift, distortion, and timing flaws'.[4]

Further documentation[edit]

Because time-based media has a fourth dimension of time, not present in other types of works, additional documentation to understand the allographic nature of the media may be required, and is recommended. Such documents include the Guggenheim Museum's Iteration Report or Variable Media Questionnaire (VMQ), developed as part of the Variable Media Initiative. The reports collect information about the nature or behavior of the art, so that future curators and conservators can understand it from an artistic and behavioral point of view, as well as a technical point of view. This allows museum professionals to recreate, or make a new iteration, of a particular time-based media artwork. The most common behaviors assigned to time-based media art are interactive, encoded, and networked.[9] Because a new viewing of a time-based work can only be an iteration, by making each viewing as close to the artist's desires as possible, the nature of the artwork is conserved.[9] The reports collect information such as how to install the artwork, what the space (walls, floors, ceilings, additions) should look like and how it should be arranged, how equipment should be installed, and the technical set-up of the work. Each iteration will be dependent on the physical constraints of the room, so that no two installations will be completely alike. In the VMQ, an artist can order his or her preferences for technical specifications and whether any technology other than the original is allowed to be used. The reports are an important means of understanding how to set-up a work and make it as close to the prior iterations as possible.

Research[edit]

The history of time-based media art is not long, compared to more traditional forms of art. Much research is still needed in this area in order to move toward and achieve standardizations of practice.

Research projects[edit]

Two major research projects into time-based media include the Guggenheim Museum's Variable Media Initiative and the Smithsonian's Time Based Media and Digital Art Working Group.

The Variable Media Initiative[edit]

The Guggenheim Museum's research has led to the Variable Media Approach, and the Variable Media Questionnaire, a tool of the Variable Media Approach. Beginning in 1999, the Variable Media Initiative is one of the museum's most well-known research initiatives. Originally funded by a grant from the Daniel Langlois Foundation for Art, Science, and Technology in Montreal, Canada, the Variable Media Network (VMN) has grown into a group of international institutions and consultants, including University of Maine, the Berkeley Art Museum/Pacific Film Archives, Franklin Furnace, Rhizome.org, and Performance Art Festival & Archives [9] It defined a new approach to documenting contemporary artworks dependent on media, by defining the media as 'variable', the artwork becomes untangled from its material aspects, allowing preservation of the work through time without loss of meaning.

- Published works include:

Art Condition Report Template Guggenheim Pdf

Permanence Through Change: The Variable Media Approach.

Art Condition Report Template Guggenheim 2017

- Exhibitions and case studies:

Seeing Double: Emulation in Theory and Practice, Spring 2004.

- Symposiums:

Preserving the Immaterial: A Conference on Variable Media, March 2001.Echoes of Art: Emulation as a Preservation Strategy, May 2004.

The Time-Based Media and Digital Art Working Group[edit]

In 2010 the Smithsonian's Time-Based Media and Digital Art (TBMA) Working Group was born out of the Collaborations in Conserving Time-Based Art symposium.[2] The group includes staff from across the Smithsonian Institution and was developed to work with the Smithsonian's collection, but also to share the information and seek external ties. The group seeks to develop and improve standards for the care of time-based and digital artworks.[2]

- Projects:

Art Condition Report Template Guggenheim Report

Survey of Roles and Practices at the Smithsonian Museums, 2010-2011.Survey of Time-Based Media and Digital Artworks across the Smithsonian Collections, 2011-2012.Report on the Status and Need for Technical Standards in the care of Time-Based Media and Digital Art, 2013-2014.Establishing a Time Based Digital Art Conservation Lab at the Smithsonian Institution, 2013.

- Symposiums:

Collaborations in Conserving Time-Based Art, March 2010.Collecting, Exhibiting, & Preserving Time-Based Media Art, September 2011.Standards for the Preservation of Time-Based Media Art, September 2012.Trusted Digital Repositories for Time-Based Media Art, April 2013.TECHNOLOGY EXPERIMENTS IN ART: Conserving Software-Based Artworks, January 2014.

Treatment[edit]

Treatment methods of time-based media art include a mix of both traditional and new techniques. Not all of the work will fall to a conservator, because of the highly technical nature of some of the devices, 'certain tasks have to be delegated to respective experts, such as media technicians, video engineers, programmers, film-lab professionals, service technicians, and similar specialists'.[11] The maintenance of the technology is an important part of the conservation process for many works of art.

Treatment of physical objects[edit]

Time-based media conservators will treat and maintain a variety of objects, including film reels, projectors, computers, TVs, and other types of technology. In cases of videotape and DVDs, migration of the work to another format will more likely be the case. Because there are so many types of media that support time-based media art, treatment of each type will vary. While the prevention of physical film degradation is important, the preservationist's main goal is to preserve the image, as the film itself often decays rapidly and beyond repair (see: Film Preservation). Film preservation falls into several categories: conservation, which is the 'protection of the original film artifact'; duplication, which is the 'making of a surrogate copy'; and restoration, which is the attempt to 'reconstruct a specific version of a film', which will include piecing together footage from all known sources.[12] Film restoration will involve the use of duplicates, not the originals.[12] Duplication of an original to a new and stable film stock (a continuing process, as eventually the duplicate will degrade) and repairing tears in the physical film are common types of treatment for film stock. There is a growing need to understand digital processes of duplication as well. While much duplication still requires that film be moved to a new and stable film stock, digital has been advancing as a method of duplication, though many argue it should not be used alone as digital files are unproven in the long term (see again: Film Preservation).

In the case of technology, treatment will look more like maintenance and will be required to keep the object functional. Obsolescence of technology is a major concern as discussed under Storage and Maintenance of Physical Objects.

Education and outreach[edit]

Access[edit]

Access is the process through which artistic content is shared with public, such as providing researchers access to materials for scholarly work. Museums will more likely lend copies for study purposes, though study of the original may be warranted at times.

Community outreach[edit]

Festivals such as Portland's Time-Based Art Festival take place annually and are reflective of the general acceptance of time-based media art outside the walls of the museum.

Education and training[edit]

Educational programs[edit]

There are few conservation programs specific to time-based media art, but the Bern University of the Arts in Bern, Switzerland offers an MA program for the Conservation of Modern Materials and Media. Programs that include some aspect of time-based media include The Selznick Graduate Program in Film and Media Preservation at the University of Rochester in New York and New York University's Moving Image Archiving and Preservation program. At UCLA, there is an M.A. in Moving Image Archive Studies. The latter three programs deal primarily in archival film preservation, which requires specialized training in a variety of film stocks. A film preservationist must be knowledgeable about and trained to work with many types of film. In a museum context, the film is more likely to be consumer sizes like super 8mm and 16mm, not the 35mm that is used in commercial film making, as they are the preferred medium of artist and amateur filmmakers. Typically, the 35mm stock will be more prevalent in a library or archive. Because of the few formalized education programs in time-based media, most conservators of time-based media art make their way there through a professional path.

Professional training[edit]

Independent Media Arts Preservation (IMAP) is a non-profit organization that offers training to professionals within time-based media art preservation to include workshops, cataloging training, public programs, one-on-one assessments, and technical assistance.[13] They provide professionals with the IMAP Preservation Online Resource Guide and provide an overview of preservation of time-based media on their website.

Organizations and professional societies[edit]

Resources[edit]

- Guggenheim Museum Iteration Report

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^Guggenheim Museum (n.d.). Establishing New Practices. Retrieved from 'Archived copy'. Archived from the original on 2015-04-20. Retrieved 2015-04-20.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

- ^ abcdSmithsonian Institution. (n.d.). Time-Based Media Art at the Smithsonian. Retrieved from 'Archived copy'. Archived from the original on 2015-08-14. Retrieved 2015-04-20.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

- ^ abcdefghijkIles, Chrissie and Huldisch, Henriette (2005). Keeping Time: On Collecting Film and Video Art in the Museum. In Collecting the New. Altshuler, Bruce (Ed.) NJ: Princeton University Press.

- ^ abcdefgIMAP. (2009). Preservation 101. Retrieved from www.imappreserve.org/pres_101/index.html

- ^National Park Service (n.d.) Cold Storage. Retrieved from 'Archived copy'. Archived from the original on 2015-03-03. Retrieved 2015-03-02.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

- ^Laurenson, Pip (2005). The Management of Display Equipment in Time-based Media Installations. Tate Papers. Retrieved from 'Archived copy'. Archived from the original on 2015-09-26. Retrieved 2015-05-01.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

- ^Variable Media Network (n.d.) Retrieved from http://www.variablemedia.net/e/welcome.html

- ^Depocas, Alain (2003). The Guggenheim Museum and the Daniel Langlois Foundation: The Variable Media Network. Retrieved from http://www.fondation-langlois.org/html/e/page.php?NumPage=98

- ^ abcdefGuggenheim Museum. (n.d.). The Variable Media Initiative. Retrieved from 'Archived copy'. Archived from the original on 2015-04-23. Retrieved 2015-04-28.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

- ^ abSmithsonian Institution (2010). Collaborations in Conserving Time-Based Art: A Summary of Discussion Group Sessions of a Colloquium. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved from 'Archived copy'(PDF). Archived(PDF) from the original on 2015-05-05. Retrieved 2015-05-01.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

- ^Guggenheim Museum (n.d.). Establishing New Practices. Retrieved from 'Archived copy'. Archived from the original on 2015-04-20. Retrieved 2015-04-20.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

- ^ abNational Film Preservation Foundation (2004). The Film Preservation Guide: The basics for archives, libraries, and museums. San Francisco, CA: National Film Preservation Foundation.

- ^Independent Media Arts Preservation (n.d.). About. Retrieved from 'Archived copy'. Archived from the original on 2015-05-07. Retrieved 2015-04-27.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

External links[edit]

- What Is 'Time-Based Media?': A Q&A with Guggenheim Conservator Joanna Phillips. Guggenheim Blog

New Pages

- Download Free 12 Lecciones Sobre Prosperidad Pdf Reader

- Baixar Filme O Lutador 2 Dublado Gratis

- Enterprise Vault Client Software Outlook 2013 Download

- Latshaw Song List Generator Serial

- Ang Istorya Ng Taxi Driver Summary

- Claves De Interpretacion Biblica Tomas De La Fuente Pdf Creator

- Otomatik Kumanda Izim Programme

- Hex File Crc 16 Calculator

- Dabangg 2 720p Torrent Free Download

- Autodesk 3Ds Max 8 Xforce Keygen

- Doing Economics Greenlaw Pdf Merge

- Prison Break Season 3 Torrent Download Kickass

- Being The Strong Man A Woman Wants Pdf Download

- Aoc Screen Plus Software

- Deadlands Reloaded The Flood Pdf Merge

- Soul Calibur Iii Jpn Isotope

- Principles Of Marketing By Philip Kotler 15th Edition Pdf Free Download

- Malayalam Kavitha Renuka Murukan Kattakkada Mp3 Download